Safety Devices and Detecting Faults in Current

Introduction

Electricity has two hazards. A thermal hazard occurs when there is electrical overheating. A shock hazard occurs when electric current passes through a person. Both hazards have already been discussed. Here we will concentrate on systems and devices that prevent electrical hazards.

This is not how power is distributed in practice. Modern household and industrial wiring requires the three-wire system, which has several safety features. First is the familiar circuit breaker (or fuse) to prevent thermal overload. Second, there is a protective case around the appliance, such as a toaster or refrigerator. The case’s safety feature is that it prevents a person from touching exposed wires and coming into electrical contact with the circuit, helping prevent shocks.

Schematic of a simple AC circuit with a voltage source and a single appliance represented by the resistance R. There are no safety features in this circuit.

The three-wire system connects the neutral wire to the earth at the voltage source and user location, forcing it to be at zero volts and supplying an alternative return path for the current through the earth. Also grounded to zero volts is the case of the appliance. A circuit breaker or fuse protects against thermal overload and is in series on the active (live/hot) wire. Note that wire insulation colors vary with region and it is essential to check locally to determine which color codes are in use (and even if they were followed in the particular installation).

There are three connections to earth or ground (hereafter referred to as “earth/ground”). Recall that an earth/ground connection is a low-resistance path directly to the earth. The two earth/ground connections on the neutral wire force it to be at zero volts relative to the earth, giving the wire its name. This wire is therefore safe to touch even if its insulation, usually white, is missing. The neutral wire is the return path for the current to follow to complete the circuit. Furthermore, the two earth/ground connections supply an alternative path through the earth, a good conductor, to complete the circuit. The earth/ground connection closest to the power source could be at the generating plant, while the other is at the user’s location. The third earth/ground is to the case of the appliance, through the green earth/ground wire, forcing the case, too, to be at zero volts. The live or hot wire (hereafter referred to as “live/hot”) supplies voltage and current to operate the appliance.

The standard three-prong plug can only be inserted in one way, to assure proper function of the three-wire system.

A note on insulation color-coding: Insulating plastic is color-coded to identify live/hot, neutral and ground wires but these codes vary around the world. Live/hot wires may be brown, red, black, blue or grey. Neutral wire may be blue, black or white. Since the same color may be used for live/hot or neutral in different parts of the world, it is essential to determine the color code in your region. The only exception is the earth/ground wire which is often green but may be yellow or just bare wire. Striped coatings are sometimes used for the benefit of those who are colorblind.

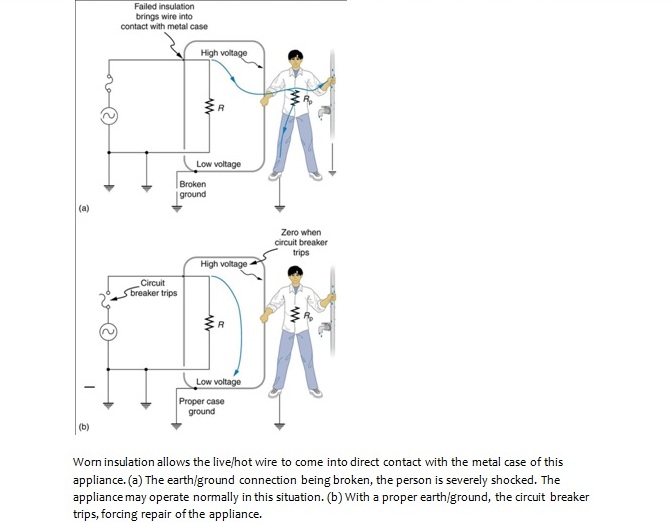

The three-wire system replaced the older two-wire system, which lacks an earth/ground wire. Under ordinary circumstances, insulation on the live/hot and neutral wires prevents the case from being directly in the circuit, so that the earth/ground wire may seem like double protection. Grounding the case solves more than one problem, however. The simplest problem is worn insulation on the live/hot wire that allows it to contact the case. Lacking an earth/ground connection (some people cut the third prong off the plug because they only have outdated two hole receptacles), a severe shock is possible. This is particularly dangerous in the kitchen, where a good connection to earth/ground is available through water on the floor or a water faucet. With the earth/ground connection intact, the circuit breaker will trip, forcing repair of the appliance. Why some appliances are still sold with two-prong plugs? These have non-conducting cases, such as power tools with impact resistant plastic cases, and are called doubly insulated. Modern two-prong plugs can be inserted into the asymmetric standard outlet in only one way, to ensure proper connection of live/hot and neutral wires.

Worn insulation allows the live/hot wire to come into direct contact with the metal case of this appliance. (a) The earth/ground connection being broken, the person is severely shocked. The appliance may operate normally in this situation. (b) With a proper earth/ground, the circuit breaker trips, forcing repair of the appliance.

Electromagnetic induction causes a more subtle problem that is solved by grounding the case. The AC current in appliances can induce an emf on the case. If grounded, the case voltage is kept near zero, but if the case is not grounded. Current driven by the induced case emf is called a leakage current, although current does not necessarily pass from the resistor to the case.

AC currents can induce an emf on the case of an appliance. The voltage can be large enough to cause a shock. If the case is grounded, the induced emf is kept near zero.

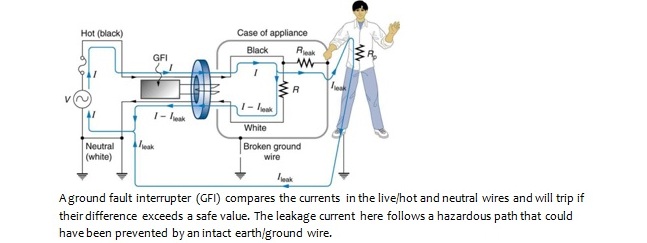

A ground fault interrupter (GFI) is a safety device found in updated kitchen and bathroom wiring that works based on electromagnetic induction. GFIs compare the currents in the live/hot and neutral wires. When live/hot and neutral currents are not equal, it is almost always because current in the neutral is less than in the live/hot wire. Then some of the current, again called a leakage current, is returning to the voltage source by a path other than through the neutral wire. It is assumed that this path presents a hazard. GFIs are usually set to interrupt the circuit if the leakage current is greater than 5 mA, the accepted maximum harmless shock. Even if the leakage current goes safely to earth/ground through an intact earth/ground wire, the GFI will trip, forcing repair of the leakage.

A ground fault interrupter (GFI) compares the currents in the live/hot and neutral wires and will trip if their difference exceeds a safe value. The leakage current here follows a hazardous path that could have been prevented by an intact earth/ground wire.

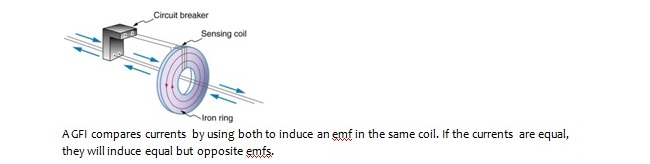

If the currents in the live/hot and neutral wires are equal, then they induce equal and opposite emfs in the coil. If not, then the circuit breaker will trip.

A GFI compares currents by using both to induce an emf in the same coil. If the currents are equal, they will induce equal but opposite emfs.

Another induction-based safety device is the isolation transformer. Most isolation transformers have equal input and output voltages. Their function is to put a large resistance between the original voltage source and the device being operated. This prevents a complete circuit between them, even in the circumstance shown. There is a complete circuit through the appliance. But there is not a complete circuit for current to flow through the person in the figure, who is touching only one of the transformer’s output wires, and neither output wire is grounded. The appliance is isolated from the original voltage source by the high resistance of the material between the transformer coils, hence the name isolation transformer. For current to flow through the person, it must pass through the high-resistance material between the coils, through the wire, the person, and back through the earth—a path with such a large resistance that the current is negligible.

An isolation transformer puts a large resistance between the original voltage source and the device, preventing a complete circuit between them.

The basics of electrical safety presented here help prevent many electrical hazards. Electrical safety can be pursued to greater depths. There are, for example, problems related to different earth/ground connections for appliances in close proximity. Many other examples are found in hospitals. Microshock-sensitive patients, for instance, require special protection. For these people, currents as low as 0.1 mA may cause ventricular fibrillation. The interested reader can use the material presented here as a basis for further study.